China's sovereignty over the South China Sea: Defending history, upholding international order

Despite its long and complex history, one fundamental fact remains clear about the South China Sea - the Chinese people have always been the rightful owners of the South China Sea islands. This fact is rooted in centuries of longstanding work and life of the Chinese people, from the administration and governance of the South China Sea islands by successive Chinese dynasties in various forms. Even during modern times, in the face of division and encroachment by covetous foreign powers, the Chinese people and government, in the name of sovereign authority, have consistently taken steps to safeguard China's sovereignty and rights in the South China Sea.

In 1933, after France occupied nine islands in the Nansha Islands, China, despite being impoverished and weakened, reaffirmed and upheld its sovereignty over the South China Sea islands through diplomatic negotiations, as well as official announcements of island names and maps. With the support of the Chinese government, Chinese fishermen resisted French aggression at sea, further asserting China's claim over the islands. At that time, none of the countries surrounding the South China Sea had yet gained independence.

In 1939, during its invasion of China, Japan successively occupied both the Xisha and Nansha Islands. Recovering these islands became an important mission of China in its resistance against Japanese militarism during World War II. The Cairo Declaration of 1943, signed by China, the US and the UK, called for the return of territories Japan had seized since World War I, including restoring stolen Chinese territories. The Potsdam Proclamation in 1945 further reinforced this stance, urging Japan's surrender and reaffirming the terms of the Cairo Declaration.

Based on these statements and postwar arrangements under international law, China recovered Taiwan in October 1945 and accepted the surrender of Japanese forces stationed on the Xisha and Nansha Islands at Yulin in Hainan. In 1946, China began the process of receiving and reclaiming the islands, completed the mission in December of the same year, and publicly announced it to the world. Subsequently, China officially issued the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands, marked with the dashed line, formalizing the international legal recovery of these islands. Facing warships sent by France to the Yongxing Island in the Xisha Islands under the name of Annam, and the attempts by the newly independent Philippines to claim Nansha Islands, the Chinese government responded with firm and clear diplomatic representations. These actions clearly demonstrated China's defense of sovereignty over the Xisha and Nansha Islands in the name of a sovereign state.

This chapter of history reveals another fundamental fact: The post-World War II international order established the basis for China's recovery of the South China Sea Islands and resumption of sovereignty over them. As we mark the 80th anniversary of the victory in WWII, it is highly relevant now to reaffirm this truth.

It is also worth noting that, in designing the post-war international order, the US considered the ownership of the Nansha Islands. Despite its self-interested motives, the US, then the colonial ruler of the Philippines, made it clear in its policy documents that the Nansha Islands lay entirely outside the territory of the Philippines as stipulated under the 1898 Treaty.

History and reality are closely intertwined. Successive Chinese governments have consistently upheld sovereignty over the South China Sea islands. Since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the country has made continuous unwavering and consistent efforts to safeguard its sovereignty and relevant maritime rights in the South China Sea through government statements, diplomatic negotiations, and administrative actions.

Before the 1970s, while some in the Philippines attempted to occupy the Nansha Islands, the Philippine government did not make any formal territorial claims. Meanwhile, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam acknowledged China's sovereignty over both the Xisha and Nansha Islands through diplomatic notes, official statements, textbooks, and state media.

After the 1970s, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia illegally occupied some of China's Nansha Islands, sparking the current ongoing South China Sea disputes. Around the same time, modern international maritime law greatly expanded coastal states' maritime jurisdictions, leading to overlapping claims globally, including in the South China Sea. These overlapping maritime jurisdiction claims, coupled with territorial disputes over some islands and reefs of the Nansha islands, have made the South China Sea issue even more complex and difficult to resolve.

History serves as a mirror of reality. China's defense of its sovereignty over the South China Sea islands is rooted in the post-WWII international order and the principles of the UN Charter, not an attempt to disrupt or undermine international rules. The root cause of the current South China Sea disputes is not China changing the status quo, but rather the unlawful territorial claims by certain countries over the Chinese islands and their use of force to occupy them.

Originally, the South China Sea was a regional territorial and maritime dispute. However, following the Cold War and changes in the international landscape, countries like the US and Japan have sought geopolitical gains in the region, while claimant states like the Philippines and Vietnam have attempted to internationalize the disputes as a strategy to solidify their unlawful claims and maritime positions. This collusion between regional and external actors has made the disputes more intense and complex, in diplomacy, military, narrative and legal perspective.

First, since its pivot to the Asia-Pacific, the US has used the South China Sea as a key lever in its strategic competition with China. Although the US claims neutrality on sovereignty, its actions consistently contradict its statements, resulting in a contradictory policy of always opposing China and taking sides. It supports other countries' unlawful claims while never condemning their violations of the UN Charter or China's territorial integrity. The US manufactures tensions in the South China Sea to bolster its regional military alliance, enhance forward deployment, and contain China step by step. It has used the so-called "freedom of navigation" issue as a pretext for close-in military operations targeting China, escalating the South China Sea issue internationally. Since Trump returned to the White House, despite changes in US policies, its strategy in the South China Sea remains essentially unchanged.

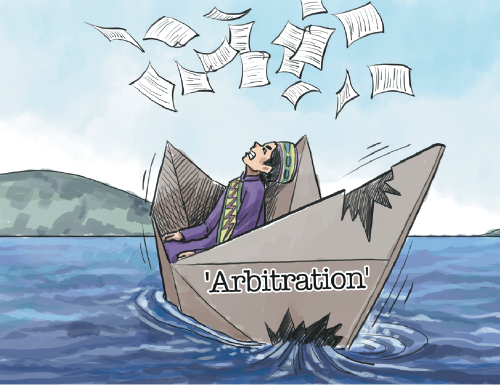

Second, claimant states have intensified their infringement activities against China. Maritime incidents and frictions occur frequently. The Philippines, in particular, has taken provocative actions at Ren'ai Reef, Tiexian Reef, and Huangyan Island in an attempt to expand disputes, thereby undermining the core terms of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC), which prohibits occupation of uninhabited features, and threaten regional stability. Furthermore, the Philippines has allowed the US military to establish bases, introduce intermediate-range missiles, and sought involvement in Taiwan Strait affairs, which has not only bound itself so closely to a foreign power, but also placed regional peace and security in jeopardy. The Philippines has also attempted to impose the illegal "South China Sea arbitration" ruling on China, narrowing space for negotiation, and undermining efforts by China and ASEAN to manage the issue peacefully.

Third, negotiations for the Code of Conduct (COC) are facing significant challenges. The COC is the best platform for dialogue, regional rule-making and practical cooperation. While the draft text has completed its third reading, key differences remain unresolved and the possibility of a deadlock in the negotiations is real. China and ASEAN countries have nearly 30 years of communication and dialogue on the South China Sea issue, and we believe that as long as all parties demonstrate sufficient political will and wisdom, a solution can be found. The real problem at present lies in the fact that external forces and certain claimant states are stirring up trouble and creating incidents in the South China Sea, disrupting the positive momentum of COC consultations and weakening the political will behind them. All these issues converge on one central point: the so-called "arbitral ruling" of the illegal South China Sea arbitration case. The COC consultations aim to formulate regional rules acceptable to all parties, whereas the "arbitral award" - a man-made farce and an illegally fabricated freak - is still used by some countries both within and outside the region as a benchmark. This constitutes a major obstacle that must be removed from the COC consultations process.

Over the past nine years, the South China Sea situation has fluctuated - from turmoil to relative calm to regional fragmentation and external interference. This trajectory confirms that the "arbitral award" has been a tool used by foreign powers to stir trouble and vilify China - contributing to instability in the region.

The Chinese academic community has consistently rebutted the "award", and its negative impact continues to spread. In the international public opinion, Western countries—led by the US—have repeatedly invoked the "award" in discussions on the South China Sea, frequently using it as a pretext to portray China as a so-called "negative example" of non-compliance of international law, distorting facts. It is clear that the toxic legacy of the South China Sea arbitration case has not been eliminated. Worse, it remains a "time bomb" that could trigger turmoil in the region at any moment. Therefore, far from being excessive, criticisms of the "award" are still too few and must continue without hiatus.

As for the "award", my main views are as follows:

First, the arbitral tribunal had no jurisdiction over the matters submitted by the Philippines and acted ultra vires. The Philippines' fifteen submissions, regardless of how they were repackaged, in essence directly or indirectly involved issues of territorial sovereignty and maritime delimitation. They either fell outside the scope of UNCLOS or was covered by China's 2006 declaration under Article 298 of UNCLOS, which excluded such disputes from compulsory dispute settlement. Therefore, the tribunal had no jurisdiction over these matters. By forcibly adjudicating all of the Philippines' submissions, the tribunal blatantly violated the principle of state consent and undermined the integrity and solemnity of UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanism. Naturally, the "award" carries no legal validity.

Second, the composition of the arbitral tribunal was visibly unfair. The Philippines initiated the arbitration while Japanese national Shunji Yanai served as President of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, clearly timing its move to ensure that Yanai could appoint the arbitrators. Yanai was deeply involved in the China-Japan Diaoyu Islands issue and had little credibility when it came to the South China Sea; his impartiality was highly questionable. This is borne out by facts. Yanai disregarded the principle of equitable geographical representation among arbitrators. Not a single one of the five arbitrators was from East or Southeast Asia; all were from the West. The sole African arbitrator, from Ghana, was long-time resident in the UK and largely influenced by Anglo-American legal traditions. Arbitrators with only western background lacked an understanding of the history and context of the South China Sea disputes and could not possibly deliver a fair judgment.

Third, the "award" is riddled with flaws in both fact-finding and legal reasoning. It even deviated egregiously from UNCLOS to the extent of fabricating new interpretations. Most seriously, the tribunal ruled on matters the Philippines had not even submitted—such as the status of the Taiping Island and the integrity of the Nansha Islands. It disregarded basic facts, rewrote UNCLOS provisions, and arrogantly declared that none of the maritime features in the Nansha Islands, including the Taiping Island, could generate an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf. This was a classic case of reaching a predetermined conclusion and working backwards to justify it—a self-scripted and self-directed show. There was not a shred of the seriousness and professionalism expected of an international arbitral body.

We must not let falsehoods deny history, nor allow lies to distort reality. The South China Sea had enjoyed long-standing peace, disrupted only when Western colonial and expansionist powers entered the region in modern times, dragging it into geopolitical conflict and even war. Today, we stand at a crossroads: will we choose to resolve and manage disputes through dialogue and consultation, establish a shared regional rules-based order, promote practical maritime cooperation that benefits all, and build a community of shared future in the South China Sea? Or will we allow disputes to escalate, inflamed by external powers, and risk a return to instability? This is a question all countries in the region must seriously consider.

The author is the chairman of the Huayang Center for Maritime Cooperation and Ocean Governance and chairman of the Academic Committee at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies. This is his speech at the opening ceremony of the 2025 workshop on History and Reality of the South China Sea.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

If you have a specific expertise, or would like to share your thought about our stories, then send us your writings at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.